When the Grand Berry closed in 2022, Fort Worth Magazine penned a lament, calling the short-lived cinema the city’s “first and only arthouse theater.”

But was it really the first?

I was skeptical and to satisfy my skepticism, I took a dive into old newspaper archives. And I’ve concluded that the answer is: Probably not?

In the late 1970s, Fort Worth actually did get a short-lived independent cinema that rose from the (metaphorical) ashes of a former porn venue, and there’s a good argument that it was in fact the city’s first genuine art house theater.

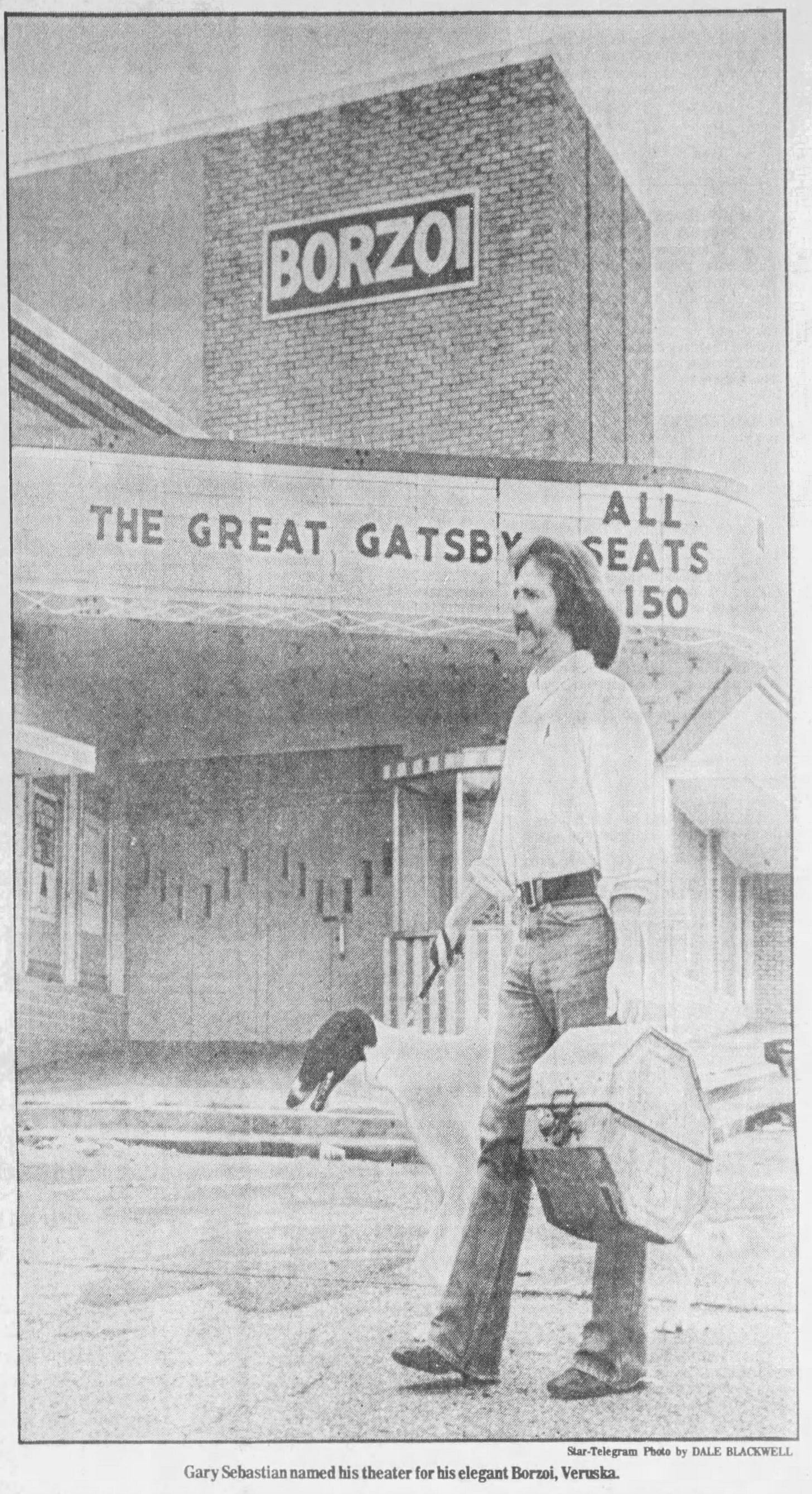

The Borzoi Theater — named for the dog breed — stood at 4137 W. Rosedale and opened in April 1977. A few months later, it received a mostly laudatory profile in the Star-Telegram, which remarked that the venue “may not have a panoramic screen, or an elaborate lobby” but that it sure had “the most elegant mascot of any theater in the city.” (The theater’s name was inspired by a specific Borzoi, a pooch named Veruska, that belonged to one of the owners.)

More importantly, at least for the newspaper’s more genteel readership, the Star-Telegram announced that the Borzoi was “porn no more” — i.e., that it was trying to shed its reputation as a former purveyor of skin flicks.

Some backstory is necessary: Before the Borzoi became the Borzoi, the theater was known as The Capri and was showing exclusively Spanish-language movies. But before that, the building was a venue for X-rated films. Unsurprisingly, such a place attracted controversy. (This is Fort Worth. Of course it’s unsurprising.)

In 1962, officers in the city’s vice squad confiscated a ribald picture called Scanty Panties that was scheduled to play at the Capri after the local film censor board (a not uncommon institution in cities during the early-to-mid-twentieth century) decided it was “too adult for adults,” as one headline put it.

Then, over a decade later, police raided the theater and confiscated Deep Throat, the infamous and influential pornographic film. The raid led to obscenity charges for the theater’s ticket taker, a man named Alvin Neal Risley, who was eventually convicted by a jury, fined $500, and jailed for 30 days. The Star-Telegram covered his trial aggressively, running daily stories about the courtroom proceedings, and the reporters captured some fascinating details, like the fact that jurors had to watch Deep Throat in the courtroom so they could decide whether it was actually obscene. (It seems ironic — and very funny — given that the prosecution’s goal was to, you know, suppress the film.)

What’s galling about the case, apart from the basic act of censorship, is that, judging from the newspaper accounts of the trial, Risley became the fall guy for the theater’s ownership and management, the men who actually profited from screening the film. His bosses certainly didn’t go on trial for obscenity! (Though a court did later bar them from showing any more explicit films at the venue.) Moreover, Risley told the jury he’d only been working at the theater for three days before he was arrested.

The injustice of the obscenity trial aside, what interests me most about the Capri Theater is that its owners actually did try to refashion the place as an art house in the 60s, long before it became the Borzoi. According to local theater critic Perry Stewart, the theater’s manager

tried to establish the Capri as a true art house. Serious imports like Bergman's 'The Virgin Spring,' and underground works like Andy Warhol's "Lonesome Cowboys" had their first local showings at the Capri — sandwiched in between Triple-X reels.

For whatever reason, this effort doesn’t seem to have succeeded.

But let’s go back to the Borzoi: I spent quite a bit of time trying to figure out whether we can really call it an art house theater. While I couldn’t find a full list of its programming, many films that reportedly screened there, including The Godfather, The Great Gatsby, and Romeo and Juliet, don’t strike me as particularly obscure or unusual works (to put it mildly).

At the same time, Stewart, the Star-Telegram’s theater critic, praised the little theater for its more innovative choices, like Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and director Nicolas Roeg’s film about the Australian Outback, Walkabout.

The Borzoi was founded, according to Stewart, by a young trio of film buffs who were all in their 20s. They kept the ticket prices reasonable — $1.50, not at all exorbitant for the time — and seemed to treat the theater as a genuine passion project. One of the founders, Julie Kinnan, emphasized the importance of a movie house’s “social atmosphere.”

“It needs to be a place where you can relax in the lobby or sip coffee and visit instead of watching the picture and leaving,” she told the Star-Telegram.

And it was this attention to ambience that led Stewart to declare the theater “a nice alternative to the ubiquitous chain which builds its theaters so that patrons can be cattle-herded out an exit, only to find themselves furlongs away from their cars.”

In other words, the Borzoi sure does sound like a cinema intended to be a community resource, a place where people could come not just for generic, forgettable entertainment but to see films that actually made them think and maybe discuss them in company. To me, that seems to fit the definition of an art house.

Alas, it didn’t last.

Less a year after it opened, Stewart (no relation to me by the way) had to write the Borzoi’s epitaph:

If you're an aficionado of, how shall we put it: "selective cinema," you no doubt lamented the passing of the Borzoi Theater. Tucked away in a cozy corner of West Rosedale, between Clover Lane and the West Freeway, the Borzoi made a creative stab at furnishing an alternative to the normal movie house fare. As the fledgling art house closed its doors there was the usual "We'll be back" pledge. And even though the sign out front read: "Closed for Repairs," there was the feeling that here was yet another ambitious project biting the dust.

Unfortunately, Stewart was right. The Borzoi theater never reopened, at least not under that name. (One of the owners did eventually refashion the theater as The Heights, a name that actually belonged to the theater before it was even the Capri, but that’s a Lost in Panther City story for another time.)

So what killed it?

There’s no way to know for sure, without tracking down the former owners, if that’s even possible. It seems clear that the theater couldn’t become financially sustainable, perhaps because it was unable to fully shed its reputation as a place to see pornography. There’s some evidence to support that theory: At least one rant — sorry, “letter to the editor” — was published by the Star-Telegram, attributed a patron who thought the Borzoi’s films were still pornographic:

I read the write up on the Borzoi Theater. It sounded like it would be a place for the family to see some good movie entertainment.

As a family, we went to the movies and saw “The Man Who Fell From Earth.” [Note: I think the letter-writer means the 1976 film The Man Who Fell to Earth, starring David Bowie.] Midway through, it was obvious that this was not going to be family entertainment.

The owner-manager of the Borzoi described his theater as not being akin in subject matter to the Capri, of pornographic notoriety. Whether it is mild porno or hard core porno, pornography is pornography. He also stated he was so busy obtaining films he did not have time to view them.

I suggest if he intends to refer to movies presented at the Borzoi as family-type movies that he begin to do some previewing and use discretion in selection.

As I left the theater, I saw notice of forthcoming attractions promising to be even more pornographic than the movie I had just seen.

I don’t think it’s a particularly good sign that Fort Worth has allowed not just one but at least two promising independent cinemas to close over the years.

That doesn’t mean Fort Worth is totally hostile to quality film. The Modern screens great movies. The presence of the Fort Worth Film Club, of which I’m a member, is a huge boon to the city. (They’re actually not the first organization to try and set up independent film screenings in the city. But I’ll save a discussion of that group, the now-forgotten Fort Worth Film Fiends, for another time.)

But if the City of Cowboys and Culture wants to have actual culture, it needs to take an interest in supporting institutions beyond the Kimbell or whatever Taylor Sheridan is up to these days. Fort Worth will probably hit 1 million residents in the five years; surely a city of our size can find a way to support a single good movie theater?

Thanks, as always, for reading. See you next time.

P.S. I’ve written more about Fort Worth’s film culture in the past. Here are links to those pieces, which new subscribers might not have seen: