How Fort Worth censored the first black movie star

In 1910, the city banned screenings of a fight between champion boxer Jack Johnson and a white challenger. Officials feared its 'evil effects.'

Reactionary censorship is fueled by the perception that some images are inherently dangerous. Prose is hardly free from repression, but the iconoclastic impulse runs deep in Western culture, and latent suspicion periodically flares into open hostility, often exploding along preexisting social fault-lines. Images that challenge entrenched power structures or cultural norms are seen as urgent threats to be quashed.

While today's censors are fixated on erasing images of queer representation (especially in Texas), the early twentieth century features a case of censorship that defended Fort Worth’s racial hierarchy. To wit: In the summer of 1910, city officials banned a boxing film in which a black man triumphed over his white opponent. Fort Worth was rigidly segregated, and this indisputable (motion) picture of black power troubled the local structures of (do I need to say white?) authority. Then-mayor W. D. “Bill” Davis went so far as to call it “a shame to the white race.”

Here’s the story: The winning boxer was Jack Johnson, an international sports sensation and native of Galveston who was the first black prizefighter to be crowned world heavyweight champion. In his day, Johnson was “the most famous black man on the planet,” observes historian Theresa Runstedtler in her book Jack Johnson, Rebel Sojourner.

Johnson’s prominence was due in part to the burgeoning movie industry. Early filmmaking and boxing were deeply intertwined, and the new medium helped disseminate Johnson’s image to a global audience. At least one Johnson detractor complained at the time that he treated his matches primarily as performances to please the camera. Whether or not that’s true, there is a strong argument that Johnson’s widely viewed appearances on screen make him the first black movie star. (Runstedtler makes this claim, as does film scholar Dan Streible in his book Fight Pictures: A History of Boxing and Early Cinema.)

However, Johnson’s celebrity and prowess also made him a threat to white supremacy. When he defeated white heavyweight champion Tommy Burns in 1908, Johnson crossed what had been an inflexible color line in the segregated sport. Immediately, the white press and public began agitating for a new challenger who could restore the racial hierarchy, and they alighted on Jim Jeffries, a former heavyweight champion who’d retired from boxing in 1905. The press nicknamed him “the White Hope.”

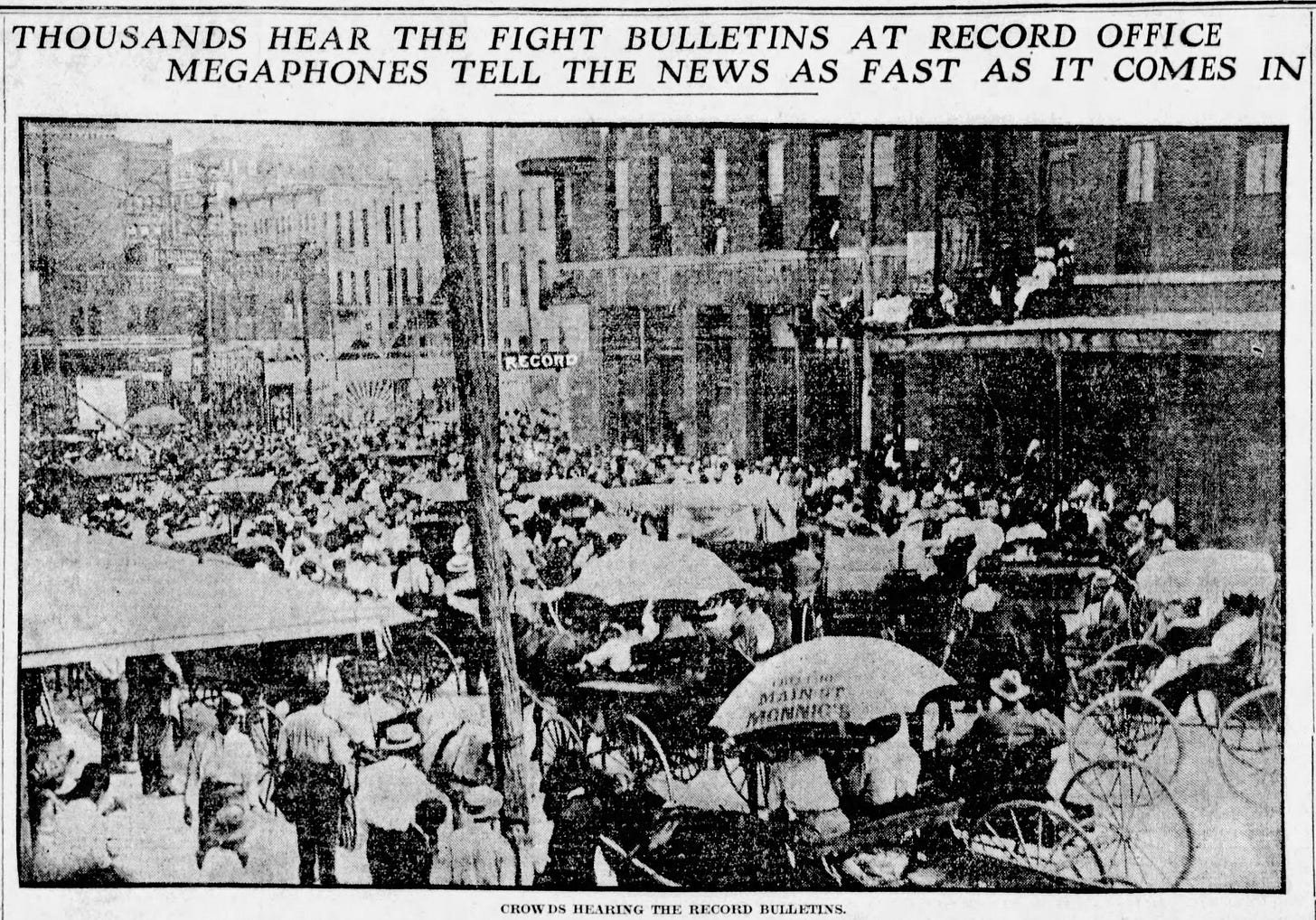

“[T]he Johnson-Jeffries match became a symbol of conflicting ideologies about race,” writes Streible in Fight Pictures. “Jeffries said he came out of retirement ‘for the sole purpose of proving that a white man is better than a negro.’” Meanwhile, “the black press and public, for their part, made Jack Johnson a signifier of race pride.” Local interest was acute, and on the day of the fight, The Fort Worth Record and Register claimed that thousands gathered near the paper’s offices to hear live reports broadcast by megaphone.

But despite intense pressure on Jeffries to deliver, the match, held in Reno, Nevada on July 4, 1910, ended with a decisive Johnson victory. An explosion of violence followed, caused mostly by white vigilante mobs who injured hundreds of mostly black men in cities across the country. Worse, somewhere between eleven and twenty-six people were killed in the aftermath, according to historian Geoffrey Ward’s biography of Johnson, Unforgivable Blackness. In Fort Worth, police arrested over 40 people after fights erupted. No one seems to have been killed, though a reporter for the Record and Register witnessed a white man mobbed by “one thousand pounds of enraged masculine avordupois [sic]” and savagely beaten for celebrating Johnson’s victory.

The much-anticipated film of the Johnson-Jeffries match also faced sweeping and widespread suppression. Fort Worth was not the only city to block screenings of the film, and the reaction here certainly mirrored broader trends. But while several scholars have traced the outlines of the national and international wave of censorship, the particular ways in which city officials justified Fort Worth’s ban are worth discussing in more detail.1

City officials clearly assumed that what was seen on screen would have a simple, causal influence on the populace, for good or ill. And to them, the Johnson-Jeffries fight heralded nothing but ill. According to the Star-Telegram:

“There are even more evil effects in moving picture shows,” said [police commissioner George Mulkey], “than is realized. They have the power of exerting much good, and yet their adverse power is tremendous.” Then he recited the instance of a 12-year-old boy recently brought before him charged with a unique burglary. The lad confessed his guilt and told the commissioner that he had reproduced the tactics employed by motion picture burglars.

Precisely what the “evil effects” of the Johnson-Jeffries film might be were left unstated. Mayor Davis was equally vague in his call for a ban — at first. He labeled himself a “friend to the moving picture shows” in general, but argued the Johnson-Jeffries fight had already proved to be a “bad influence.” He alluded to, but did not explicitly mention, the reports of violence across the country.

The next day, the mayor got more specific in his concerns. As he told the Star-Telegram on July 6, it was the precise moment of Johnson’s victory that worried him, and letting people see it happen was dangerous:

The fight is wrong … and the sane-minded people of Fort Worth know it is. The very sight of the fatal knockout blow, I am certain, would stir numbers of Fort Worth men to trouble. The rioting all over the country Monday night gave me a picture of the effect the fight films would produce and I acted before it was too late.

After the first day of fights, there were no documented reports of violence in Fort Worth connected to the film (at least not in the white newspapers that I’ve been able to access). Whether or not we want to give any credit to the mayor and city leaders is an open question.

What would’ve happened if Fort Worth hadn't censored the film? Would black residents have risen up at the sight of Johnson’s victory? This is what police commissioner Mulkey seemed to fear. But, as historians have documented, black communities reacted to news of the fight with jubilation and joy, not violence.

Would white people have enacted overt terrorism against Fort Worth’s black community, acting out some kind of twisted racial revenge fantasy? Possibly. Maybe this is what mayor Davis meant when he remarked that the film would “stir numbers of Fort Worth men to trouble.” Recall that the mayor also called the Johnson-Jeffries fight “a shame to the white race.” Perhaps, with such a vivid reminder as the film around, that shame would become unbearable and would explode into violence.

But we’ll never know because something about the image of a black boxer triumphant was just too terrifying for the powers-that-be to allow on screen.

The most prominent and easily obtainable book on Fort Worth’s black history — professor Richard Selcer’s 600-page A History of Fort Worth in Black & White, published in 2015 — spends only half a page on censorship of the Johnson-Jeffries fight film and offers no substantial insight into the stated motives of city leadership. Selcer also approaches the subject with a paternalistic frame: i.e., whether or not Jack Johnson constituted a good “role model” for the black community.

Here are the relevant passages from pages 277 and 278:

Role models on the national stage were few and far between for African Americans. One was boxer Jack Johnson, known as the ‘Galveston Giant,’ who won the heavyweight championship of the world against (white) James J. Jeffries on July 4, 1910. Johnson was the first black boxer to win the title, and wild celebration among African Americans all over the country followed. Johnson was instantly elevated to celebrity status, receiving more press coverage than all other black national figures combined. A film of the bout proved a bigger draw than any other film in cinematic history before Birth of a Nation (1915). In Fort Worth, the city commission would not even allow the film to be shown because of the incendiary subject matter—a black man thrashing a white man in the ring. Yet white fight fans who would never countenance a black champ taking the heavyweight boxing title would jam-pack black fight clubs to bet on brawlers like Dallas’ “Li’l Dynamite” and other “dusky ring artists.”

Johnson’s victory over Jeffries produced two very different reactions in Fort Worth’s black community. On the one hand, people on the street celebrated the triumph of one of their own; on the other hand, black ministers like Mount Gilead’s L.K. Williams added their voices to Mayor W.D. Davis’, denouncing Johnson from the pulpit. It was one of those rare times when black and white leaders were in complete agreement—a black man who made a living beating up white men was not a good example for the black community.