Content warning: This post quotes a historical source that uses an offensive term for a biracial person.

Fort Worth likes to imagine itself as a bastion of the Old West, but it feels more accurate to call the city a repository of Western fantasy. Tristan Ahtone, former editor in chief of the Texas Observer, once observed that:

Fort Worth’s version of the West is distinctly different from what lies beyond the 100th meridian. Outside the gunfights, saloons and rodeos, Texas longhorns roam, serving as the region’s mascots, despite being uncommon in most other Western states, like Oregon or Utah. Out of all the ungulates, a buffalo might best represent the American West. But Fort Worth has remade the West in its own image.1

The famous slogan popularized by newspaper baron and relentless city booster Amon Carter is, from this perspective, less a descriptive statement and more like an attempt to exert control over the city’s image. “Where the West Begins” is both a positive mythology residents can buy into and a way to devalue other possible understandings of Fort Worth. By omitting all the other civic identities and influences that are woven into the city’s past in favor of “Western heritage,” the statement obscures as much as it reveals.

One major omission in the city’s contemporary story about itself — or at least the shallowest, most visible versions of that story — is a genuine recognition of Fort Worth’s substantial connections to the Deep South and the region’s particularly brutal system of racial repression and exploitation. Historian and TCU graduate Jacob Olmstead, in his study of Fort Worth’s celebration of the Texas centennial, argues the city in the early twentieth century was defined by a mixture of Old South and Old West, characterizing Fort Worth as a place perched “on the environmental precipice of the West” but with strong cultural affinity for the pre–Civil War South:

Fort Worth, and Texas in general, inherited a southern past. Southern states supplied the city with most of its early Anglo pioneers who brought with them slaves, cotton, and southern ranching culture. Although home to few large plantations or slaveholders, Tarrant County (which includes Fort Worth) voted in favor of secession to preserve the institution of slavery. Following the war, former Confederates fleeing the Deep South for a better future settled in Fort Worth and Tarrant County and played a singular role in their development and the maintenance of the cultural attitudes of the Jim Crow South.2

All this helps explain why a racist film that portrayed black people as grotesque brutes, whitewashed the Confederate cause as a noble crusade, and glorified the Ku Klux Klan as saviors of the white race found a rapturous reception in Fort Worth.

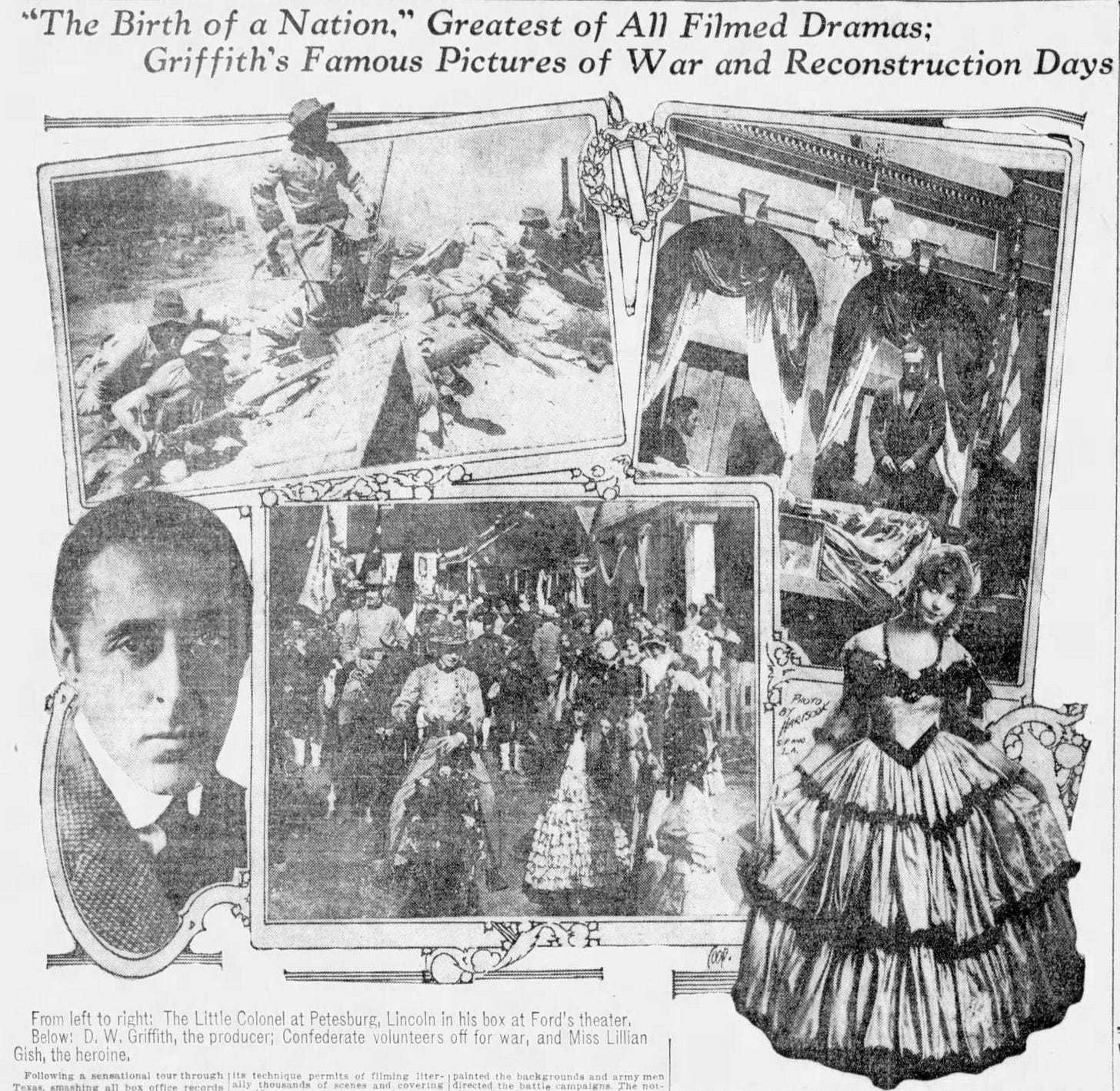

A few years before Carter first pasted “Where the West Begins” on the front page of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, his newspaper was promoting The Birth of a Nation, filmmaker D. W. Griffith’s cinematic reimagining of the Civil War and Reconstruction-era South. The film arrived in Fort Worth on November 19, 1915, and a Star-Telegram reporter who attended a screening at the Byers Opera House gave this account of the audience’s enthusiastic response:

The Byers didn’t seem like a theater Thursday night. It didn’t even seem like a picture show, though the attraction was a picture. Its atmosphere was that of a circus or wild west show.

“The Birth of a Nation,” David W. Griffith’s much heralded masterpiece of the motion picture art, aroused the audience to a high pitch of enthusiasm and they gave vent to that enthusiasm. Veterans of the war Between the States, both Confederates and G. A. R.s,3 saw in the scenes many of the stirring engagements through which they had passed and true pictures of reconstruction days that brought back vividly to their minds the horror of those terrible times. And they gave vent in characteristic fashion to their feelings. Yells, whistles and handclapping rent the air and hisses greeted the work of the m****** whom the Northern leader tried to place in control of Southern whites.

It seems the film provided a concrete source of validation for Fort Worth’s white residents, justifying their racial resentment and their perception of Reconstruction as a “terrible” era.

The city was probably no worse in its initial reaction to The Birth of a Nation than others in Texas; newspaper accounts reported that the film was an enormous commercial hit, and theaters were so packed in Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio that hundreds of prospective viewers were turned away. But Fort Worth’s embrace of the film was marked by the Star-Telegram’s pointed efforts to enshrine it as an authentic work of history and a campaign to convince students to see the film.

After screening in the city four times over the previous four years, The Birth of a Nation returned to Fort Worth in 1919 for what was labeled its “farewell visit.” That same year, the NAACP, which had been organizing against the film since it first premiered, successfully lobbied Dallas to censor it on the grounds that the film “was based upon racial antagonism,” according to the Dallas Express, the city’s influential black newspaper.4

If there was any similar opposition to The Birth of a Nation in Fort Worth, I’ve so far been unable to find a record of it. Instead, a few days after the Dallas Board of Censors ordered the Hippodrome Theatre to scrap its plans for screening the film, the Star-Telegram announced it was organizing an essay contest for all history students in Fort Worth’s public and private schools. The topic: “Why Every Student of American History Should See ‘The Birth of a Nation’.”

Why an essay contest?

It’s impossible to state, with any certainty, exactly what motivated Carter and the Star-Telegram editors, other than their obvious admiration for the film. But institutions hold essay contests for ideological reasons: Students are incentivized — through money, scholarships, or the promise of prestige — to write about a narrow set of ideas or values that matter to the people in charge of dispensing the rewards. (Just look at the Ayn Rand Institute’s contemporary essay contest for high schoolers, which lavishes cash on students willing to publicly praise Rand’s libertarian philosophy.)

The main function of the Star-Telegram’s essay contest was to reinforce the idea that The Birth of a Nation was a work of serious history, despite its fictional characters. The newspaper emphasized, over and over in its promotion of the competition, that the film was supposedly a window into the past. It rhapsodized about one student who said they had seen The Birth of a Nation four times and quoted their description of it as “one of the best and most educational pictures ever produced.” The prompt also closed down the possibility of debate: The question was not whether every student of American history should see the film, but rather why they should.

The winning essay, published in the pages of the Star-Telegram, had this to say:

What is the birth of a nation? It does not take place when a newly discovered country is settled either by few or by many colonists. Nor does it take place when a colony rebels against a tyrant, but the birth of a nation occurs when the people of a country act as one person, undivided in nothing, united in everything.

The Star-Telegram ultimately chose to elevate a vision of history that prioritized unity above every other value — a very Fort Worth way of thinking.

The winning student goes on to praise Griffith’s film for its supposed “historical accuracy” and praises its ability to help students get beyond the “maze of battles and dates” that constitutes the Civil War, allowing them to delve more deeply into studying the nation’s history. The essay concludes on this note: “The student obtains a neutral viewpoint from this picture. He realizes that both sections believed themselves right.”

In other words, the winning student was channelling the “both sides had a point” mentality that still afflicts revisionist Southern history about the Civil War; it mirrors the brand of fallacious “states’ rights” arguments that persist in reactionary institutions like the Texas Civil War Museum in White Settlement.

The Star-Telegram’s essay contest and the broader reality it suggests — namely, that city tastemakers were, in the early twentieth century, invested in promoting Lost Cause mythology — should complicate any simplistic picture of Fort Worth as the place “Where the West Begins.”

Nothing I say here is an argument for uncritically celebrating the racist, secessionist parts of the city’s past. To be clear: It’s a good thing that the Confederate flag, a rancid hate symbol, was finally banned from the Stockyards this year.

But I do worry that the failure to properly acknowledge Fort Worth’s place within the American South makes it harder to talk honestly about projects like reparations for slavery and Jim Crow–era oppression or material efforts to dismantle institutional racism, especially now that the vague promises about racial equity city officials made in the wake of George Floyd’s murder have faded into irrelevance.

As long as Fort Worth pretends that rodeos and cattle drives are its only authentic heritage, the city is continuing a long tradition of pointing at fiction and calling it history.

Ahtone was writing for High Country News, a magazine that covers the actual American West.

A reference to members of the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.), an organization for Union veterans.

Regardless of whether censorship was the right strategy, the NAACP was not wrong to fear that the film would provoke white animosity towards black residents. The Birth of a Nation bears a significant share of responsibility for the rebirth of the KKK in 1920s. Civil rights historian Philip Dray recounts the immediate fervor provoked by the film’s release in his book At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America, a meticulous history of the post-Reconstruction South:

At the Los Angeles preview of The Birth of a Nation, actors made up as Klansmen had ridden by on horses as a promotional stunt. By the time the film premiered in Atlanta in fall 1915, real-life horsemen in full regalia from a newly revived Klan paraded up and down Peachtree Street before the theater. “Ku Klux Fever” gripped the South, and Klan hats and other souvenirs were sold. Watching the movie, Southern audiences whooped the rebel yell and, at one showing, emptied their revolvers into the screen. In rural areas, The Birth of a Nation swept through almost as if it were a traveling circus, with extras dressed in period garb hawking the movie on village streets. Where no movie theater existed, special excursion trains were arranged to bring country people en masse into urban areas to take part in this national rite of passage. Feeding on the excitement, Klan recruiters worked the theater lobbies.