The history of Fort Worth’s Isis Theater isn’t nearly as convoluted as the theater’s financial situation, which, as the Fort Worth Report has documented, is a multi-million dollar dumpster fire. But the historical record is both fascinating and perplexing.

First, let’s get a few names straight.

There’s the Downtown Cowtown at the Isis, the incoherently branded modern iteration that shut down last week. (That name has always raised too many questions: Why “downtown cowtown” when the city’s actual downtown is three miles south? Was “downtown cowtown” chosen purely for the juvenile rhyme? Is the theater named the Isis, or is the theater at the Isis? Do words have meaning?)

Before the theater was refurbished in 2021, the location was officially known as the New Isis Theater. This version opened in 1936 and shut down in 1988, after which the building languished for three decades. The New Isis replaced the original theater, which was known simply as the Isis. For its part, the old Isis closed and reopened at least once between 1914 and 1935 when it was finally torn down and replaced.

Speaking of names: Why Isis?

Here’s how Jack Gordon, a longtime local entertainment columnist, told the story in a Fort Worth Press article, as quoted in a 1973 issue of Box Office Magazine:

When [L.C. Tidball] prepared to open the original Isis in 1913 . . . he looked through a book which listed the names of every theater in New York. Tidball had to have a name that hadn’t been grabbed by other movie houses in Fort Worth, such as the Orpheum, Rex, Egyptian. Then his eye fell on the name Isis in the New York theatre directory. He had never seen or heard that name before. He named his Fort Worth theatre [sic] the New Isis.

Little errors aside — the old Isis actually opened in 1914 and the name “New Isis” was only used after the theater reopened in 1936 — the origin story is mostly notable for how underwhelming and banal it is. “Isis” does fit a pattern of theater names from the same era that tried to evoke grandeur, exoticism, or both: Aside from the Orpheum, Rex, and Egyptian, the Isis’s competitors in Fort Worth during the 1910s and 1920s included the Hippodrome, the Majestic, the Palace, and the Queen, among others. But the fact that Tidball, who financed the Isis’s construction and took over as owner in 1916, chose the name seemingly at random and mostly because it had been previously overlooked is not exactly indicative of some grand vision. Trend chasing? Yes. Strong imagination? Not so much.

The original Isis was also not a top-tier theater. It earned no special distinction in a 1921 full-page newspaper ad dedicated to promoting Fort Worth’s theaters. The ad, which was funded by a group of retailers trying to boost consumer spending at local businesses, saved its praise for the Hippodrome and the Palace, describing the two as “the highest types of temples devoted to the efficient presentation of photoplays.” (Whatever that means.) Perhaps more telling is the fact that in 1915 the Isis was twice convicted and fined in criminal court for showing films on Sundays. It seemingly violated one of Texas’s so-called “blue laws,” which outlawed fun and other illicit activities on the lord’s day. At the time, the theater’s lawyer told a Star-Telegram reporter that the business would only be breaking the law if it charged admission: The Isis’s defense seemed to hinge on the fact that, instead of making people buy tickets on Sundays, it had asked for “donations.”

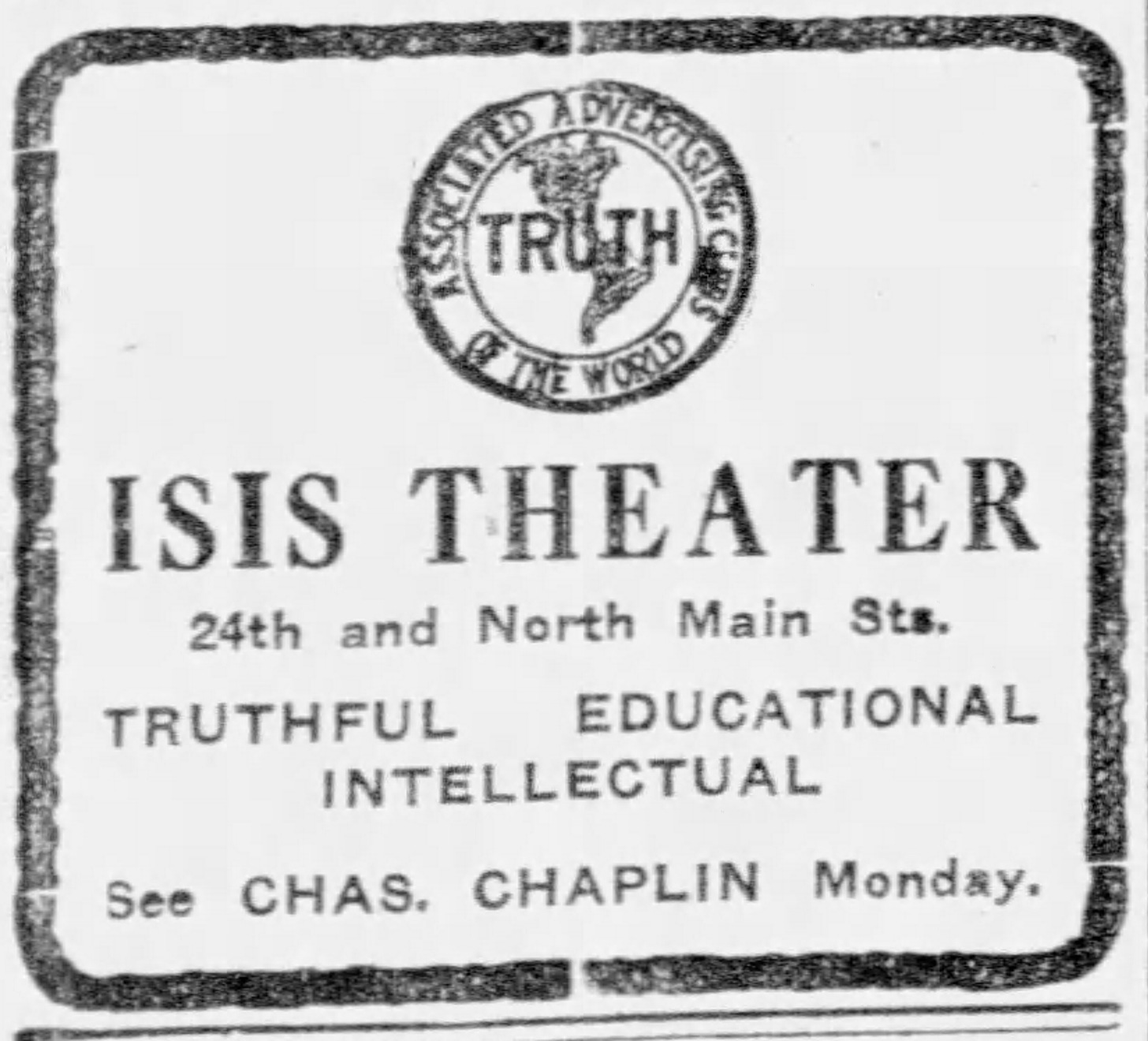

Hilariously, in the short few weeks between court cases, the Isis held a fundraiser for the All Saints’ Catholic church’s altar society. The Star-Telegram, which reported on the event, didn’t mention any particular motivation, but it’s hard not to see the move as a public relations strategy to offset the perception that the theater was detrimental to public morals. (If such fundraisers were a common practice for the theater, it wasn’t documented by the newspaper.) The Isis also ran an ad in the Star-Telegram around this time that proclaimed the theater was “truthful,” “educational,” and “intellectual.” Yeah, okay!

Why the Isis closed in 1935 isn’t entirely clear. Recent news reports about the theater usually say a fire destroyed the building, but I’ve been unable to find any actual documentation of this. The history page on the Downtown Cowtown’s website makes this claim, and it’s probably the source used by most news stories. But there was no mention of such a fire in the Star-Telegram at the time. If there was really a fire, this would’ve been a major and uncharacteristic oversight for the newspaper: It was quite diligent about documenting fires — especially fires of that magnitude — in the 1930s.

In fact, the first reference to a 1935 fire that I’ve been able to track down came six decades later. In 1995, a fire in the Stockyards caused minor smoke damage to the New Isis, and the Star-Telegram’s story mentions that the original Isis “opened in 1914 but burned in 1935.” It doesn’t attribute the information, however.

This is quite strange because the newspaper repeatedly covered the New Isis in the twentieth century. A feature in 1983 about the theater’s longevity is a good example. That story documented the theater’s history in extensive detail but made no reference to any fire. In 1965, the paper ran a retrospective interview with then-owner L.C. Tidball a few years before he would eventually sell the theater. Again, no mention of a fire. There was even a feature in 1946 about the New Isis’s tenth anniversary birthday celebration. The story recounted the consequences of a catastrophic flood that hit the building in 1942. But no fire.

Perhaps the current Downtown Cowtown owners have documentation of this fire or maybe there’s other proof buried in an archive I haven’t found yet; it’s possible. But it seems highly unlikely that the Star-Telegram would’ve waited sixty years to mention this high-profile disaster.

So what really happened? Here’s my best guess:

There was a fire reported in the Isis on March 7, 1929 that caused $1500 worth of damage (or about $27,000 in today’s dollars). Likewise, the original theater did close for good in 1935 — that’s quite clear. Perhaps the 1929 fire caused enough damage that the Isis was never able to fully recover. It makes sense that, years later, people might misremember the events as more closely linked than they actually were, which is probably how the 1935 fire anecdote came to be; historical memory is like an extended game of telephone even at the best of times.

But that’s just speculation on my part. For now, the fire remains an unsolved mystery.

The New Isis opened in March 1936. It was shiny at first. Literally: The interior of the theater, which was twice as large as the building it replaced, was reportedly painted gold.

While this may have represented a more upscale era, it didn’t last. In 1942, floodwaters from Marine Creek smashed through the area, flooding everything within a six-block radius of North Main and Exchange Avenue, including the New Isis. While the theater put up a “business as usual” sign a day after the waters receded, the flood caused an estimated $8800 in damage (about $160,000 in today’s dollars).

The business seemingly struggled to fully recover after that. Tidball was pessimistic in a 1965 interview that ran under the headline: “After the Flood: Theater Owner Recalls Better Days on N. Side.” The longtime owner said that, during his tenure, the theater’s most successful year was 1918. “But times have changed,” the Star-Telegram reporter observed. “Saturday nights on the North Side aren’t as lively as some Tidball remembers there.”

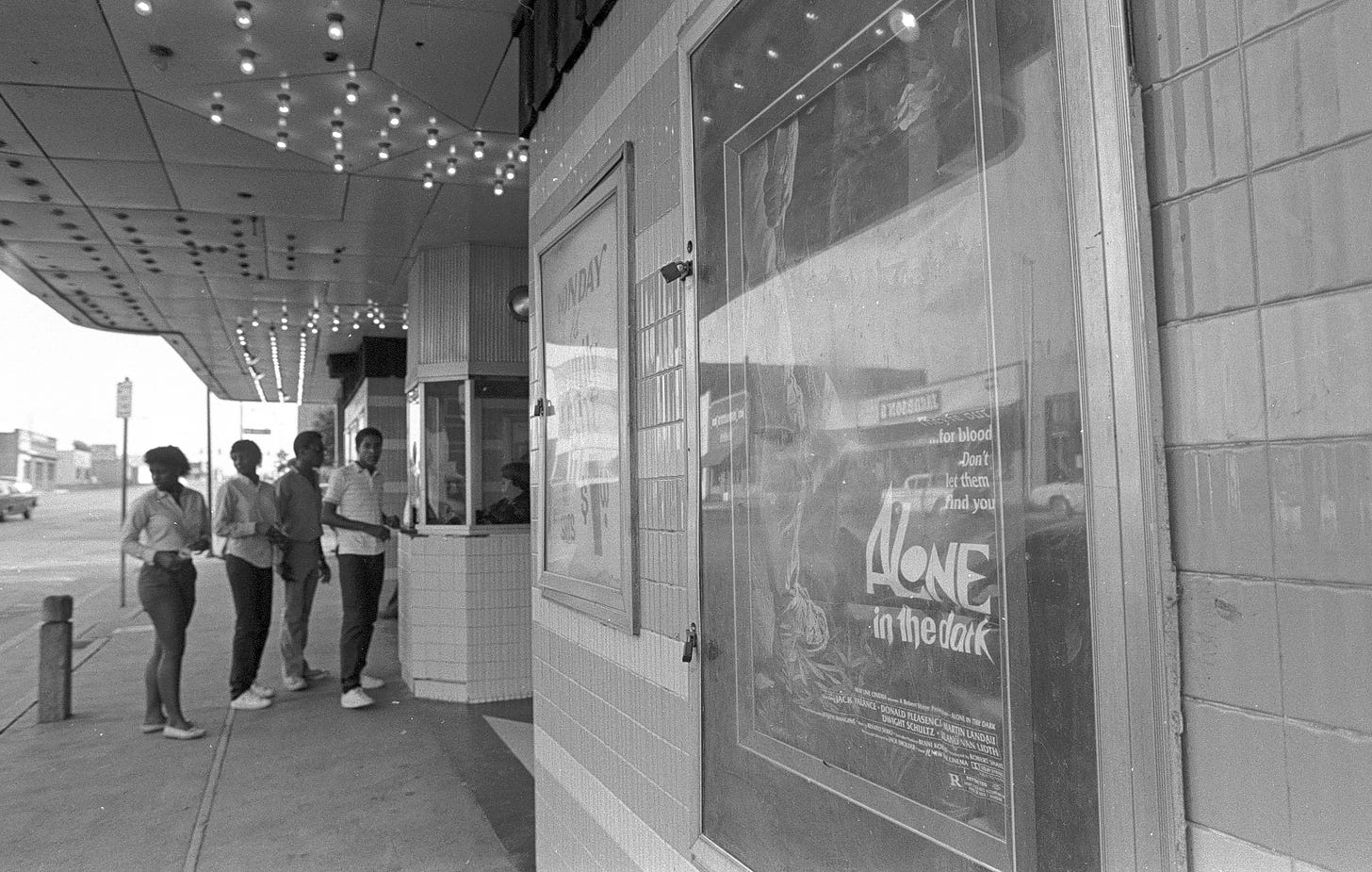

It’s interesting, though perhaps not surprising, that the theater remained continuously in the hands of white owners, despite the fact that its patrons were by the 1970s and 80s mostly people of color. The theater, like others in Fort Worth, was segregated well into the mid-twentieth century, and the Stockyards-area had been a Hispanic neighborhood since at least the 1920s. While I couldn’t find a record of when the New Isis officially desegregated, Harold Griffith, who purchased the theater in 1970, told the Star-Telegram in 1983 that the balcony’s top rows, where African Americans were originally forced to sit, were “still there but used for anybody, thank God.”

The New Isis became somewhat notorious in the 1970s for showing explicit films, upsetting some North Side residents. As the Star-Telegram reported in 1974:

Small children carried signs reading “We Like Movies Too,” outside the Isis Theater at 2403 N. Main more than two hours Sunday afternoon, protesting the theater’s showing of what they called “all those R-Rated films.”

The picketers were members of a new North Side group calling itself Familias Unidas, which consists of 15 to 20 families who would prefer to see the Isis run more G-rated films.

Years later, the Fort Worth Weekly looked back on the same period:

A former Northside resident recalled how his non-English-speaking grandmother took him and his young cousins to watch what they thought was an animated kiddie flick in the mid-1970s. She quickly gathered up her brood and fled the theater in disgust a few minutes into Fritz the Cat, the first X-rated animated feature, based on the underground comic books of Robert Crumb.

As with the original Isis, what exactly doomed the New Isis is hard to say for sure, but the neighborhood’s discontent with the theater’s programming probably didn’t help. Griffith told the Star-Telegram in 1983 that his mostly low-income patrons were hit hard by the economic recession of the early 1980s, and also blamed changes to the theater business and cable television. The New Isis fell slowly but inexorably into disrepair. As the newspaper reported in October of that year:

[A]las, the New Isis ceased being “new” quite a while ago. It can no longer hold a projector to its sleek, modern, multi-screen counterparts in malls across the town. It long ago lost the stately shine of the Ridglea Theater or even the Seventh Street. . . The theater’s some 900 narrow, wooden seats have been abused a few times too often, and show it. Paint hides just so many dirty words scrawled on theater walls.

The New Isis finally shuttered for good in 1988.

It’s easy to look back on the Isis with nostalgia. As the Weekly observed in 2004 story about a (failed) attempt to reopen the theater:

Many long-time Fort Worth residents recall watching Hopalong Cassidy movies there in the 1940s and Roy Rogers in the 1950s. Fifteen cents would buy a kid four hours’ worth of movies, serials, newsreels, and cartoons. Fort Worth attorney and city councilman Jim Lane, who watched westerns there as a boy, characterized the theater as “magnificent” with its Egyptian décor, including exotic wall lights shaped like papyrus flowers.

But did this sense of majesty and grandeur that Jim Lane describes ever really exist? Or was the Isis always kind of a cheap, second-rate theater that used gold paint to pretend otherwise? Labelling a building “historic” confers on it a sense of dignity that is sometimes unwarranted.

To be clear, I do want the theater to be preserved, and tearing it down would be a tragedy. But I’d love for Fort Worth to embrace the seedy, disreputable parts of the Isis’s past: The fact that it was once a lawless establishment trying to circumvent religious morality laws and that it pissed off the community by showing X-rated cartoons is way more interesting than the theater’s pretentious and orientalist faux-Egyptian name and decor. It’s proof that the place had life and vitality and that it mattered to the community, even as an object of anger. The same can’t be said of the now-shuttered Downtown Cowtown, which rarely seemed to attract a crowd of any kind. (Though allegedly not paying its workers is certainly a form of lawlessness and something that fills me with rage.)

The New Isis was one of novelist Larry McMurtry’s favorite theaters, largely because it was the kind of place that would play awful movies in front of indecorous audiences. The Pulitzer-Prize-winning author wrote in his 1987 book Film Flam that:

Long before I knew that I actively preferred bad movies to good I recognized that I much preferred the places bad movies played to the places where art films were usually shown. I have always hated art theaters, art audiences, screening rooms, suburban theaters, and, indeed, decorous moviegoers of any ilk; apparently some severe Methodist suspicion of all fanciness still lurks in my psyche. My favorite theaters in the whole world are the Yale on Washington Avenue in Houston and the New Isis, near the stockyards in Fort Worth . . . [A]ll across America there are fringe theaters like the Yale and the New Isis, usually in border areas where blacks, Chinese, chicanos and rednecks mix, and for anyone with either a taste for street life or participatory theater, these are the places to see movies. The audience will more than compensate for whatever turgidities there may be in the film.

This specific era of “fringe theaters” isn’t coming back. (That’s for the best: McMurtry also relates an anecdote about a time he saw a man play a fatal game of Russian roulette in one of his favorite theaters; not the Isis, as far as I can tell.) But if the Isis ever reopens — as the New New Isis? — it needs to at least refashion itself as terrible in an interesting way. Perhaps that’s impossible. Maybe its proximity to the tourist hellscape of the Stockyards means it’s fated to become an outpost of kitsch and Western nostalgia. But we can at least hope for a better brand of bad theater in the future.

Really enjoyed this article! Rhea and I recently discovered the theater-before we learned about its financial woes and mistreatment of staff. We watched When Harry Met Sally on their screen on an impromptu Valentines Day date. I’m happy we got to experience whatever iteration of the Isis was then, and I hope someone can really do it justice in the future.

Thoroughly enjoyed learning about the history of this place!