It just sounds like cruelty to me

The regular razing of tent cities and homeless encampments is a slow-burning news story in Fort Worth.

I was gonna start writing a thing about a local news story that made me angry. Then I remembered this is supposed to be a history newsletter, so I spent hours digging through old newspaper clips and edited my about page to give myself permission to write about the present — and ended up back where I started. Except now I’m also depressed and have 2,000 words to inflict on you.

It is depressing to read 30 years’ worth of Star-Telegram editorials saying some version of “we have a homeless problem in this city, let’s fix it” or “we have a plan to fix homelessness, let’s fund it.” I now have a whole folder of these things dating back to 1987, which was shortly after Ronald Reagan decimated federal spending on housing for the poor and then said things like “the homeless who are homeless, you might say, by choice.” Three decades later and the Star-Telegram was still writing, “It will take a village to end homelessness — and money.”

Even the editorial board eventually got depressed or maybe bored and gave up its exhortations after 2017. As far as I can tell the last time the newspaper seriously raised its institutional voice on the subject of the city’s unhoused residents was in 2019 when it endorsed new police powers to remove “unsightly camps” from private property. Since then, silence but perhaps that’s for the best.

Before I get too cynical, let me honor my obligation to fairness and note that Fort Worth is full of well-meaning nonprofits and nice people who try and sometimes succeed in getting people into houses.

But not always. Sometimes this city says fuck it, let’s smash their faces with a boot instead.

Here’s what a local CBS producer saw the other day:

On the morning of Dec. 30, 2022, Fort Worth police and code compliance workers arrived with squad cars and bulldozers at the I-35 overpass over E. Lancaster Ave. The homeless residents were told to pack their things and leave. The bulldozers swept in a few minutes later and wiped away what remained of a community of sorts that had been there for years. The people there had nowhere to go, but they couldn't stay there.

One of the people living there, a young woman pushing a cart full of clothes and other supplies, said the only warning she had was from a representative from the city earlier in the week. The representative informed the woman that she and the other residents would need to leave before Friday. The problem was that she - and many of the others living there had nowhere to go.

Some of them had been there for weeks, others for months. Some had been homeless for years, others for less than a month. They all said that the city did not offer any help nor any resources for them to follow up with. Their community was demolished and torn apart as they stood watching helplessly, left to figure out what to do next by themselves.

Most of them said that this was not unusual. They told me that there was often a lack of a communication from the city and police. Earlier this month when temperatures dropped into the 20s and low teens, the camp's now-former residents said nobody from the local or county governments came to offer help or resources.

The regular razing of tent cities and homeless encampments is a slow-burning news story in Fort Worth. Every few years or so the city gears up for another big sweep in the name of public safety or public health and local news outlets sometimes take notice.

In 2017, the city took out a dozen camps on the east side, issued criminal trespass warnings, and made arrests. Then-councilman W.B. Zimmerman called it “a great first step” during a city council work session, though a step toward what wasn’t made clear. Zimmerman said homelessness was “epidemic citywide,” and there was also a lot of talk in that council meeting about “cleaning up” sites where unhoused people were living. Sometimes that did seem to mean literally cleaning up trash. But I dunno man, there were human beings there too and talking about them this way always makes me uneasy.

In 2015, the city evicted a large community near East Vickery and South Riverside citing, among other things, alleged drug use, sex work, animal cruelty, and assaults at the camp. The Star-Telegram ran a good story that humanized the residents and pointed out that the city was just shuffling the problems around, not fixing them. It also quoted the Fort Worth’s code compliance director as saying the sweep would help push people “toward the services and the lifestyle that will break the chains that will get them out of homelessness.”

I’m sure it did not but okay.

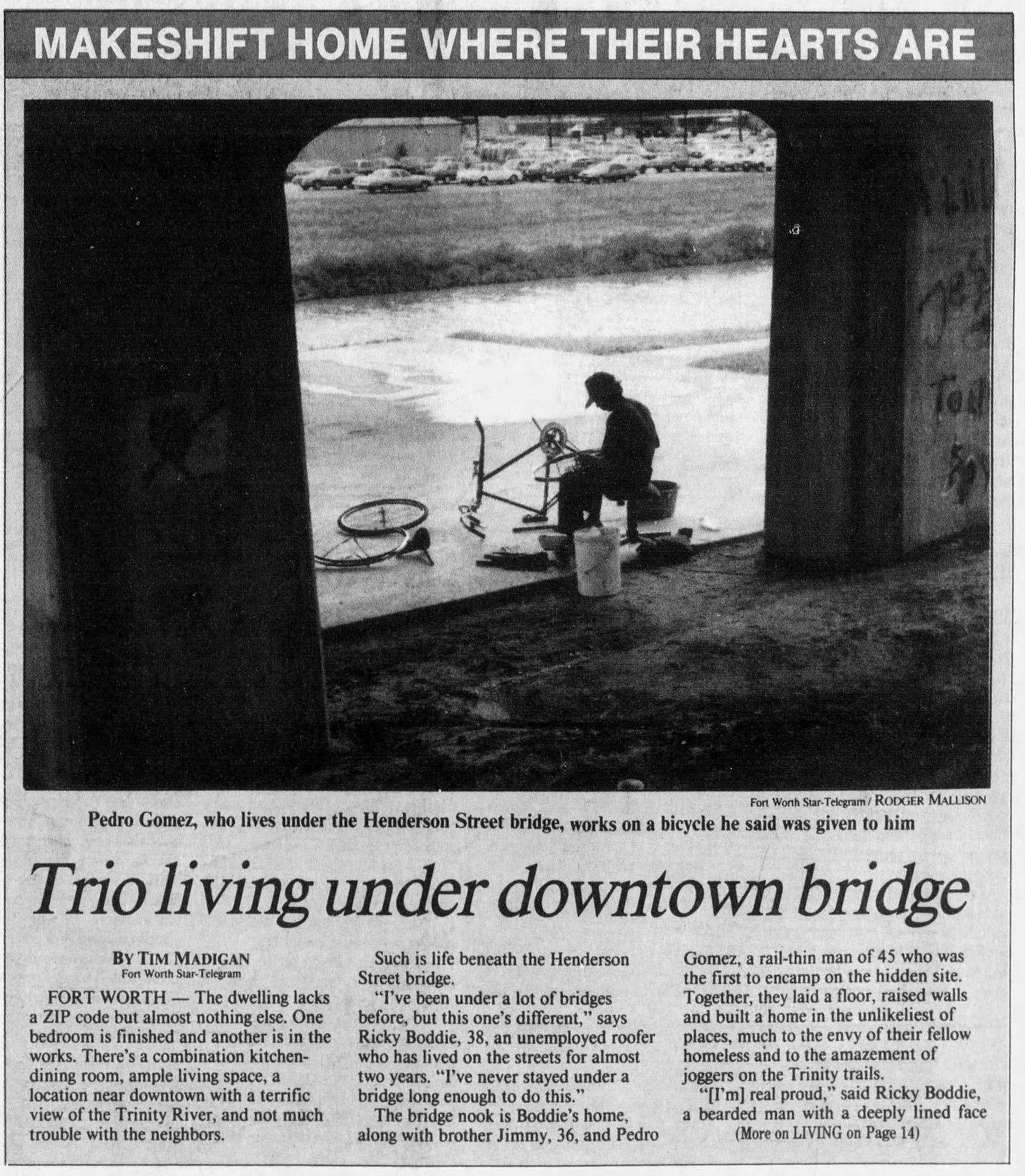

I’ll share one more story I found in the archives, this one from 1991. That September, reporter Tim Madigan profiled a trio of men living below the Henderson Street bridge. This was no tent and sleeping bag setup but an elaborate makeshift housing development, complete with furnished kitchen, bedroom, dining room and plans for future expansion. The men were clearly aware of their own precarity and actively discouraged others from joining them. “Tramps and hobos come by and they want to spend the night with you,” one of the men told Madigan. “But if you get a bunch of people around here, that’s the way they run you off.”

Fort Worth police sergeant L.T. Murphy told Madigan the cops were keeping an eye on the house but he showed little interest in bothering the men: “We could chase them out of there and they could just go somewhere else,” Murphy told Madigan. “What are we going to do? Harass them because they’re down on their luck? I’m not.”

City leadership didn’t agree. The next day, a pair of reporters (neither of whom was Madigan) had a front page follow-up: “Bridge no longer a home,” read the headline. “3 men evicted, house is razed.” Here’s how it went down:

It was Gomez who had first envisioned turning the space underneath the bridge into a home. And it was Gomez who was the hardest to pull away from the carpeted cement dwelling, with its plywood walls, chairs, dresser, blankets, mattress.

At exactly 2 p.m., when the team of state workers descended from the bridge, the Boddie brothers moved to the side. But Gomez stayed behind to have one last meal.

He poured some milk and scooped a handful of cereal into a fuchsia plastic cup, and slowly ate his lunch.

Ignoring police officers’ warnings that time was up, Gomez finished his meal, then stood and began scrubbing the table.

He scrubbed and scrubbed until the table was spotless. Then he silently walked to the side of the bridge to join his friends.

The state workers, wearing white hard hats and black gloves, quickly moved in, kicking in walls and tossing furniture into the yellow dump truck.

It took time to pull down a wire clothesline that hung on the concrete wall and several trips to haul away things like an empty Easter basket and a pair of broken antique chairs. But within half an hour, all that remained was graffiti-covered concrete. It was just a bridge again.

I really don’t know if I’d have the guts to write a vivid, compelling narrative about an eviction my newspaper inadvertently caused. But I suppose bearing witness to their forced dispossession is a type of tribute and recompense even if it didn’t bring their house back.

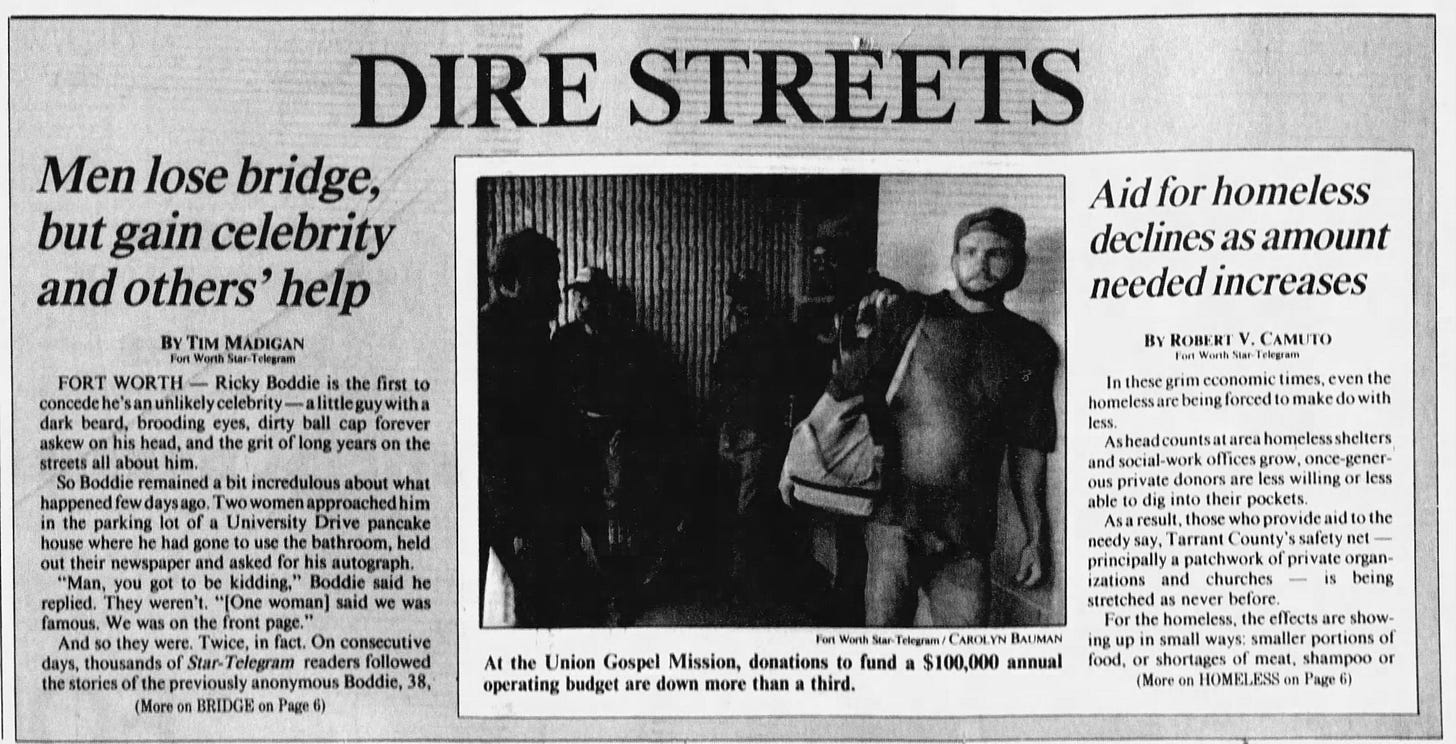

Madigan must’ve felt like shit because this is never the “impact” a reporter wants to have, though he also followed up a month later with another profile of the men, who had gained unexpected notoriety and enormous public sympathy. Outraged readers had besieged the newspaper with letters and calls over its role in the men’s ouster.

This time all parties were more discrete:

“We’re not holding any grudges,” Ricky Boddie said. “Things happen.”

As if to prove it, Boddie offered to show a reporter the site of their new camp, if its location was not revealed. The subsequent excursion led from a major thoroughfare, to a side street, then hundreds of feet into a dense thicket where foliage blots out the sun.

“As long as nobody knows where we are, nobody can run us off,” Boddie explained as he led.

Let’s talk about the big picture for a moment.

In 2015, the city’s code compliance director said Fort Worth was doing at least a hundred sweeps a year. But only one was big enough to catch the attention of local news. The vast majority went unnoticed in the public record.

How many camps were razed in 2022? I don’t know. The city probably does and with some reporting I could probably shake that number loose. But my point is this: If ripping down tents worked and was something the city took pride in, we would hear about it more often. The number of people displaced would be highlighted on the Tarrant County Homeless Coalition’s “know the facts” page, and you'd see a graphic about it on the city’s website. But it isn’t and you don’t.

There is ample evidence that razing camps without actually placing people in houses exacerbates existing problems by threatening established ties between outreach workers and homeless residents and generally making their lives more hellish and unstable. The National League of Cities, which lobbies in D.C. on behalf of local governments and provides training to officials in many cities, comes out hard against sweeps, calling them “a costly, cosmetic approach”:

If an individual is not present when an encampment is cleared, they may lose important possessions such as identification, which is needed to secure jobs and housing; tents and clothing, which provide protection from the elements; and potentially life-saving medication. Additionally, clearing an encampment can violently disrupt the social connections established within the community, potentially destabilizing familial structures that could otherwise provide needed support to unhoused individuals.

Even the threat of sweeps makes it difficult to maintain stability as people must worry about watching their possessions, or move from place-to-place to avoid sweeps rather than focusing on more productive pursuits such as securing employment, seeking treatment for mental and physical health conditions, or gaining access to more permanent housing and shelters.

The threat of sweeps is also stressful and can have significant negative health effects, such as causing individuals to lose sleep and contributing to worsening mental and physical health conditions.

Local advocates for the homeless have said the same thing in their official publications, though with less stridency because let’s face it they still have to get up and go be civil on zoom calls with city leaders who pull the trigger on these encampment raids. Here’s a measured and polite disavowal of camp sweeps from the Tarrant County Homeless Coalition’s 2017 report:

Motivational interviewing and engagement that is trauma-informed and housing-focused yield the best results, but progress can be as slow as human behavior is complex. It is not uncommon to encounter campers who struggle with significant behavioral health challenges such as Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and paranoid schizophrenia; others do not wish to be separated from a spouse or child by single-sex shelters.

Unfortunately, increased engagement from police and code enforcement tends to relocate rather than resolve a housing crisis or addiction. Increasing discomfort by forcing people to relocate frequently simply does not achieve long-term behavior change. Jail time is costly to taxpayers (about 60% more expensive than permanent supportive housing) and more tickets make it more difficult to secure housing.

Just a guess but I suspect plowing someone’s belonging into a dirt pile does not meet SAMHSA standards for trauma-informed interventions. “Increased engagement from police and code enforcement” is one way to describe this mess. Municipal cruelty strikes me as more fitting.

Further reading:

The High Cost of Clearing Tent Cities. Bloomberg.

How Houston Moved 25,000 People From the Streets Into Homes of Their Own. The New York Times

Your research went back to 1987, but I am curious about homelessness in Fort Worth in the years prior to that. I ask because I grew up in Kitchener, Ontario, Canada, attending downtown schools from 1975 to 1989. There were no homeless people in Kitchener until after provincially funded mental hospitals were closed in the late 1980s. I was downtown every day for fourteen years, but didn’t see a homeless person until 1990. Today, there hundreds of homeless people, and multiple tent cities. When the mental hospital closures were announced, everyone wondered where the poor lost souls in those facilities would go. We soon found out — they wound up on the street.

So I am curious. What is Fort Worth’s story before 1987?